Macros and Attributes

Learning objectives

- You know the different types of Rust macros

- You know how create and use your own declarative Rust macros

- You know the different types of Rust attributes and how to use them

In this part, we'll cover two topics that could be considered somewhat advanced: macros and attributes. Albeit they are more advanced than the previous topics, we thought it'd be good to cover them since we've been using macros (println!) already since the first code example of the course, and we've also been using attributes such as #[allow(unused)] to suppress warning messages in quite a few code examples or #[derive(Trait)] to auto-implement traits for types.

While Rust macros can be challenging to learn at first, they are quite common and can often be used to make code much nicer to write and read. So it's good to understand the basics and what benefits they can provide us. Also, they don't need to be the black magic that they may initially look like, but can actually be quite simple to understand and implement once getting used to their syntax and intrinsics. Nevertheless, we won't go too deep here on macros and attributes. For those interested in a more detailed take on macros (or just wanting more information and examples — it starts out simple), please take a look at The Little Book of Rust Macros by Lukas Wirth. We'll be referencing it here anyway.

Macros

Macros are a powerful feature found in many programming languages that allows generating code using rules or patterns at compile-time. In other words, writing macros is metaprogramming: writing code that writes code.

This allows for more concise and expressive code that can overcome the limitations of a language's own syntax, leading to increased productivity and maintainability. Consider for instance the #[derive(Trait)] attribute (which is actually a macro). It expands a given struct or enum with code to implement one or more traits — wouldn't it be annoying to have to constantly write impl Debug for ... for each custom type you wish to debug print? Or if you come from a Java background, where printing is done with

System.out.println("Text to be printed");wouldn't it be fun to be able to replace that with a macro call println!("Text to be printed");?

Expanding macros

To see Rust macros in action, in a way that we actually can see what happens upon a macro invocation, we can install the cargo-expand crate which gives us the convenient cargo subcommand

cargo expandNote that the cargo-expand crate documentation:

"Cargo expand relies on unstable compiler flags so it requires a nightly toolchain to be installed, though does not require nightly to be the default toolchain or the one with which cargo expand itself is executed. If the default toolchain is one other than nightly, running cargo expand will find and use nightly anyway."

The nightly toolchain can be installed with

rustup toolchain install nightlyThe rest of this section assumes you have cargo-expand installed, although it is actually just a convenient wrapper to the less convenient rustc command

cargo rustc --profile=check -- -Zunpretty=expandedAnyhow, let's try it out with a #[Derive(Debug)] and a println! macro. Copy paste the code from the following example () to the main.rs of a new Rust package and execute cargo expand in the package directory. You can also expand the macros in the Rust playground () by clicking on "Tools -> Expand macros" on the upper right hand side of the playground page.

The output of cargo expand should look like the following Rust code.

Running the code with cargo run won't work right out of the bat though. The expanded code uses nightly-only and unstable features so we need to enable those first. We can run cargo run using the nightly build with cargo +nightly run and the compiler suggests that we need the attributes #![feature(fmt_helpers_for_derive)] and #![feature(print_internals)] to enable the used unstable options. So add those in to the top of the file and run

cargo +nightly runand you should see the output

Point { x: 1, y: 2 }Don't worry if this feels like a bit much, we'll start off with much simpler macros when writing our own and keep them rather simple too. But before starting to write them, a short overview of Rust macros.

Rust macro overiew

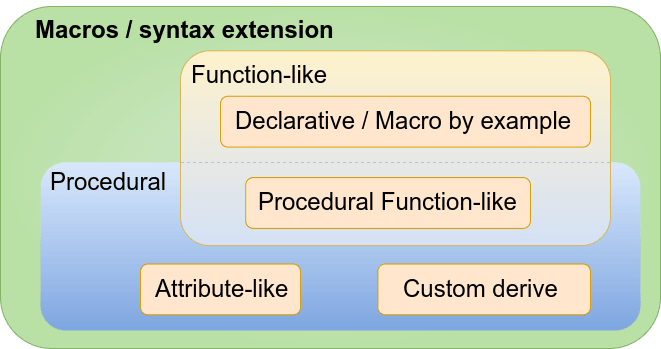

Macros in Rust fall into two categories.

- Declarative macros aka macros by example, which produce code according to a set of rules that match code patterns into code output.

- Procedural macros, which produce code by executing a Rust function that takes code as input and produces new code as output.

Macros can also be categorised by how they are invoked:

- Function-like macros, which are invoked like a function,

println!is a prime example. Function-like macros can be created by both declarative and procedural macros. - Attribute-like macros, which are invoked like an attribute. As an example, we could create an attribute

get, use e.g.#[get("/")]to map a function into a route in a web API like in the rocket crate. Attribute-like macros can be created with procedural macros. - Derive macros, which are macros that can be used with the

deriveattribute to derive custom trait implementations. Derive macros can only be created with procedural macros.

Declarative macros are more common and much simpler to define than procedural macros, which is why we'll mainly focus on them here.

Declarative macros

Declarative macros are macros that are defined by rules. They are function-like macros, meaning that they are invoked like functions, such as the familiar println! (e.g. println!("🖨️")) macro or the vec! macro (e.g. vec!["🦀", "🦀"] or vec!("🦀", "🦀") or vec{"🦀", "🦀"} — yes, the type of parentheses use for invoking function-like macros doesn't matter). In contrast to functions, declarative macros take a token tree as input instead of variables and their output is always a token tree. Simply put, their input is parsed code and the output is also parsed code.

But to get a basic idea, the code

as a token tree would look like (a token is denoted by «<token>»)

«fn» «main» «()» «{ }»

┌──────────┴────────────┐

«println» «!» «( )» «;»

┌────────┴───────┐

«"Hello, macros!"»Luckily we hardly need to understand the details of token trees or how Rust parses them to be able write our own macros. However, if your interested to know more about how macro input is parsed, check out the Source analysis section of The Little Book of Rust Macros.

Anyhow, let's start creating some of our own syntax sugar with macros!

The simplest example we can create is one that does not take any input and just expands to some code. We can do this with the macro_rules! macro.

A declarative macro aka macro-by-example aka macro_rules macro (a dear child has many names) is defined using the built-in macro macro_rules!. It takes a name for the macro and a list of rules.

Each rule consists of a pattern matcher and an expansion block.

The rules work like the match statement, the first matching rule is invoked and the pattern expanded according to the rule's expansion block. If the input pattern does not match any of the matchers, the code will not compile.

If we expand the above example with the hello! macro using the cargo expand command, we should see the main function transformed into

Compiling the expanded code requires once again running with the nightly compiler and enabling any used unstable features. We won't be showing any more expansion results in the material, but suggest expanding whenever you are unsure of the code should expand to.

Note also that cargo expand is not perfect and may not produce code that behaves the same as the compiled original code, see for instance the disclaimer at the end of the crate description.

Let's then add another rule to our macro that takes a name as input and prints a greeting to that name.

Notice that the second rule has a matcher with a $name variable. The $ indicates that the variable is a pattern variable, i.e. a fragment. And : expr is a fragment specifier which indicates that the fragment matches an expression. Both the $ and the fragment specifier are required for fragments.

If we omit the $, the pattern matcher will be a literal matcher that matches the input exactly as a stream of literal tokens.

Unlike with match statements, the compiler isn't able to notice if a macro rule is unreachable.

The third matcher will never be invoked because it only matches the literal 1 (hello!(1)) and the previous matcher catches 1 before it.

Macros do nothing but expand their input to code, so the places where we are able to use a macro depends on what the macro expands to. When we have a macro that expands to an expression, we can place it in any place we could place the expanded expression.

One important thing when writing macros, especially for bigger macros, is hygiene. Macro hygiene is about ensuring that a macro does not accidentally use or modify anything that is not intended to be used or modified by the macro. It's like hand hygiene, we wouldn't want to have our hands dirty when using our hands for example to greet a friend with a handshake.

Let's inspect a problem arising from a rather simple log! macro that uses the chrono crate for logging expressions with a time stamp to standard output.

Now in this example all works fine, but what if we have a local module chrono in the same module where we invoke macro?

We run into a conflict between the local chrono module and the imported chrono module. We can fix the problem by prepending our import with :: to ensure that we're importing the external crate and not the local module.

If we think we are out of the water now, we should hold our horses. What would happen if we have a local enum named Local and try to use it after calling log!?

Here when we try to log! Local::Person we get some compiler errors for Local being defined multiple times and Local::Person not being found in chrono::Local. This is because the import statement use ::chrono::Local; tries shadows the local Local enum with the struct::chrono::Local and the that's what we end up having in main too, not the local Local (expand the code if unsure what's goig on).

We can make the macro hygienic by wrapping the macro rule's expanded code in a block so that we don't leak any imported items or defined variables into the caller's scope.

Now, we are not clear yet. What if we try to call log! with a Local literal?

This time we run into problems inside the macro because of the use ::chrono::Local; statement inside the macro. The Local enum is once again shadowed by the chrono::Local struct and we get a similar error as in the previous case.

Its best to avoid use statements inside macros to be clear of accidental shadowing. To be extra careful, we should also consider that someone may shadow the println! macro, so we should import it properly within our own macro (even though it makes the code a bit harder to read).

Hygiene is especially important when writing macros that are intended for use by others, e.g. in a library, as it ensures that the macro does not accidentally break the code of the macro caller or cause unexpected side-effects in the program. Optimally all macros should be hygienic.

Repetitions

Let's then look at creating a macro that works like the vec! macro but for HashMaps. This will require a bit more work, because we need to be able to match multiple repetitions of the values that go inside map like we have with e.g. vec!["🎿", "🏂"].

This is also a good place to mention that the macro_rules! macros can be invoked and defined with all three kinds of parentheses: (), [], {}.

Being able to write hash_map!{"one": 1, "two": 1} to initialize a HashMap would be nice but unfortunately macro_rules! has limitations that prevent writing rules for that (: has a special meaning in the matcher). Running the below code shows which special characters are allowed between expressions in a macro rule, which allows us to see what alternatives we have.

We can however achieve something similar enough by using one of the allowed expression separator symbols (=>, ,, ;), for instance =>, instead of : to denote a key value relation — we could also simply omit the separator since the repetition separator is optional.

Note that the repetition syntax is $( $key: expr => $val: expr ),*, i.e. $( ... ) , * as in $(<repeated pattern>) <optional separator> <repetition marker>.

Notice also how the repetition is used in the expansion part of the rule: $( map.insert($key, $val); )*. This expands the code (map.insert($key, $val)) as many times as the pattern is repeated in the matched input, with $key and $val matching each iteration of the repetition one at a time.

In total, there are three different repetition markers. If you know your regular expressions, these should be familiar.

| Repetition | Meaning |

|---|---|

* | 0 or more repetitions |

+ | 1 or more repetitions |

? | 0 or 1 repetitions |

Our hashmap! macro still has a minor fault compared to the readily available HashMap::from. We can't have a trailing comma in the macro invocation, which is an unnecessary restriction and can be a bit annoying. To fix this, all we need is to match the separator with 0 or 1 repetitions at the end of the matcher.

Another option, one that also prevents creating a new hash map with hash_map!{,}, would be to leverage the first rule in another rule.

Impl macro

Function-like macros are not limited to expanding to blocks and expression, but can produce arbitrary code. Below is a common use case for declarative macros: implement a trait for a type — declarative macros are much easier to conjure up than custom derive macros.

In the below example, we have the trait Exclamated with method exclamated that returns a string with an exclamation mark appended to it. We'll create a macro to trivially implement the trait to any type that implements the ToString trait or has a to_string() method.

For the implementation generating macro, we'll want to have the matcher to match a type instead of an expression, so we'll have give the matcher fragment the specifier ty.

When a struct does not implement ToString, or we don't want our "default" implementation from the macro, we can simply implement the trait manually.

We can take our macro a step further by adding another rule which takes a field in addition to the type name. Then we can implement Exclamated for the Person struct too with the macro, or for any other struct that has a single field that should be exclamated.

Notice the specifier for the $field, ident, which matches any identifier or keyword.

The full list of available fragment specifier can be viewed in The Little Book of Rust Macros. There's for instance the lifetime and item specifiers, or the more general tt specifier which matches any token tree (a tree data structure of parsed tokens). Anyhow, we won't be needing other than the expr and ty and ident, so no need to stress out about those for this course. We'll be able to write plenty of useful macros with just the simpler specifiers, and besides, tt matches all of those and more.

Visibility

Macros are items like any other, so they can be public or private, shadowed, and are restricted to the scope they are declared in. There is a difference though in exporting macros as we can't just prepend macro_rules! with pub to make it public. Instead, we need to add the attribute #[macro_export] in front of the macro_rules! invocation. The macro will be exported at the root of the crate, so we don't need to import from the module in the main file.

Another quirk with declarative macros is that we can't use them in code that comes before the macro declaration.

If we try that anyway, we'll get an error saying that the macro is not found in the scope and an outdated suggestion of using #[macro_use] on the module/import — the #[macro_use] attribute is no longer needed in Rust editions 2018+.

Attributes

Attributes are used to add metadata to Rust code. Attributes can be either outer attributes or inner attributes.

Outer attributes affect only what comes right after the attribute. To declare an outer attribute in Rust code, we write a # and the attribute name and possible attribute parameters inside square brackets [] before the item we want to add the attribute to. As a familiar example, we can add the #[derive(Debug)] attribute (derive-attribute with parameter Debug) to a struct, we write

Inner attributes are declared like outer attributes except that they are marked with a ! after the # (e.g. #![feature(print_internals)]). Inner attributes apply to the whole item where the inner attribute is declared in and are usually found at the top of a file (the attribute is applied to the whole file).

As an example, we can disable warnings with the allow-attribute for a whole module (file) by providing it warning we want to disable as an argument — you've probably already seen your fair share of compiler warnings. The compiler tells us the name of the warning by informing us of the warn-attribute that caused the warning so that we know which warning we may or may not want to allow (the defaults are quite good for most use cases).

To demonstrate the difference between outer and inner attributes (and showcase some more linting attributes), we'll set some inner deny and forbid attributes that disallow any code that would generate a specific warning (deny gives an error instead of a warning and forbid also prevents overwriting the denial with an allow attribute). Then we'll fix the code by explicitly annotating each problematic item with a proper allow attribute or fixing the issue in case of a forbidden linting issue.

Different kinds of attributes

Rust attributes can be classified into four different types.

| Attribute type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Built-in attributes | Attributes that are built into the compiler. | #[derive(Debug)], #![warn(missing_docs)] |

| Macro attributes | Attributes that are created by procedural macros. | #[my_attribute], #![my_attribute_with_params(param1, param2)] |

| Derive macro helper attributes | Additional attributes in the scope of a derive macro that can be used to customize the derive behavior, such as attributes that determine how a field should be used for the derived trait. | #[derive(Derive)] enum Enum { #[default] DefaultEnumVariant, OtherEnumVariant } |

| Tool attributes | Attributes that are used by tools like rustfmt and clippy. | #[rustfmt::skip], #[clippy:cognitive_complexity = "10"] |

Albeit not much, this should already be enough for the basics of attributes. As you have probably noticed by now, using attributes is rather simple as long as you know what the attribute is doing. To see more detailed info, more examples, as well as the full list of built-in attributes, check the Rust reference.

Let's anyway take a look at some custom made attributes in action. Specifically, two derive attributes and some of their derive helper attributes from the crate serde which provides serialization and deserialization for Rust structs.

Serialization means transforming a data structure into a format that can be saved (e.g. to a file) or transmitted (e.g. over a network) and then reconstructed (i.e. deserialized) at a later time.

We'll also be using the serde_json crate which uses serde to serialize and deserialize Rust structs to and from JSON strings — the most common data interchange format for web APIs nowadays.

As an example, a Point struct with float fields x and y could be serialized to a JSON string like this:

{

"x": 5.0,

"y": 10.0

}To be able to serialize and deserialize a struct with serde, we need to add its Serialize and Deserialize traits to the struct. We can do this by with the derive attribute.

To run this locally, we also need to add the serde and serde_json crates to the project's Cargo.toml file. We also need the serde's "derive" feature which does not come with default features.

[dependencies]

serde = { version = "1.0.95", features = ["derive"] }

serde_json = "1.0.95"The derive macro for Serialize and Deserialize has some useful helper attributes by the name serde that we can use for instance to define default values for fields, have different names for fields than in the JSON or disallow fields not present in the struct.

In case you are interested in how the serde attributes are created, you can always check out the code in the Serde GitHub repository. It's probably best to start to with some simpler procedural macros though, links to materials with examples can be found in the next section.

Procedural macros: extra

Creating procedural macros can be quite a bit more complex than creating declarative macros since writing them usually requires parsing code as token trees. We'll have only a super short intro for procedural macros here but will provide links to external materials. There will be no exercises (it's not because the course grader does not support testing such currently, we swear...).

Procedural macros are special functions that take a TokenStream or two as input and return back a TokenStream as output. The TokenStream is a stream of TokenTrees (remember the tt fragment specifier for token tree in declarative macro matchers). The output TokenStream represents the code that the macro will expand to.

In essence, procedural macros are Rust functions that manipulate Rust code represented as token trees. Procedural macros can be used to create all three kinds of macros:

- Function-like macros (macros that expand to code that looks like a function call, the same ones that can be generated with declarative macros), defined with

#[proc_macro]attribute, - Derive macros (custom derive implementations for traits), defined with

#[proc_macro_derive] - Attribute macros (custom attributes), defined with

#[proc_macro_attribute]

However, unlike declarative macros, we can't just write a macro in a file and start using it. Procedural macros can only be defined inside a crate of the proc-macro type.

Instructions on how to create such a crate as well as a derive macro can be found both in the Rust Book and in this LogRocket blog post. At the end of the blog post you can find further links for example on how to work with token streams to create procedural macros.

A short intro and simple examples for the different kinds of procedural macros can be found in this other LogRocket blog post, and the Rust reference. The Little Book of Rust Macros has a short chapter on procedural macros also, but it is more bare-bones than the materials in the blog or the Rust reference. Likewise, the Rust Book has only very little info on the other types of macros at the end of its chapter on macros.

In case you are itching for some exercises on procedural macros, the Proc Macro workshop by David Tolnay has a few that are guided by tests. They can be difficult though.

Hi! Please help us improve the course!

Please consider the following statements and questions regarding this part of the course. We use your answers for improving the course.

I can see how the assignments and materials fit in with what I am supposed to learn.

I find most of what I learned so far interesting.

I am certain that I can learn the taught skills and knowledge.

I find that I would benefit from having explicit deadlines.

I feel overwhelmed by the amount of work.

I try out the examples outlined in the materials.

I feel that the assignments are too difficult.

I feel that I've been systematic and organized in my studying.

How many hours (estimated with a precision of half an hour) did you spend reading the material and completing the assignments for this part? (use a dot as the decimal separator, e.g 8.5)

How would you improve the material or assignments?